Health Buzz

Cotton (maltese) and Candy (phantom toy poodle) sleeping in the same position. Isn’t that adorable?

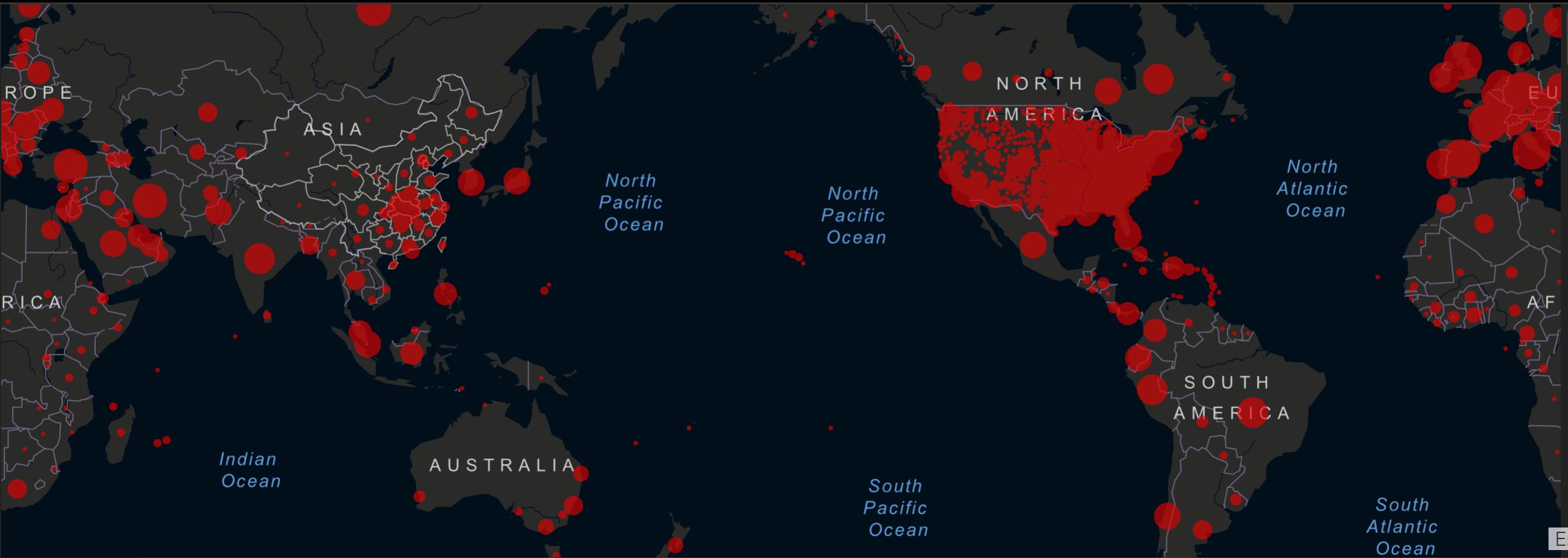

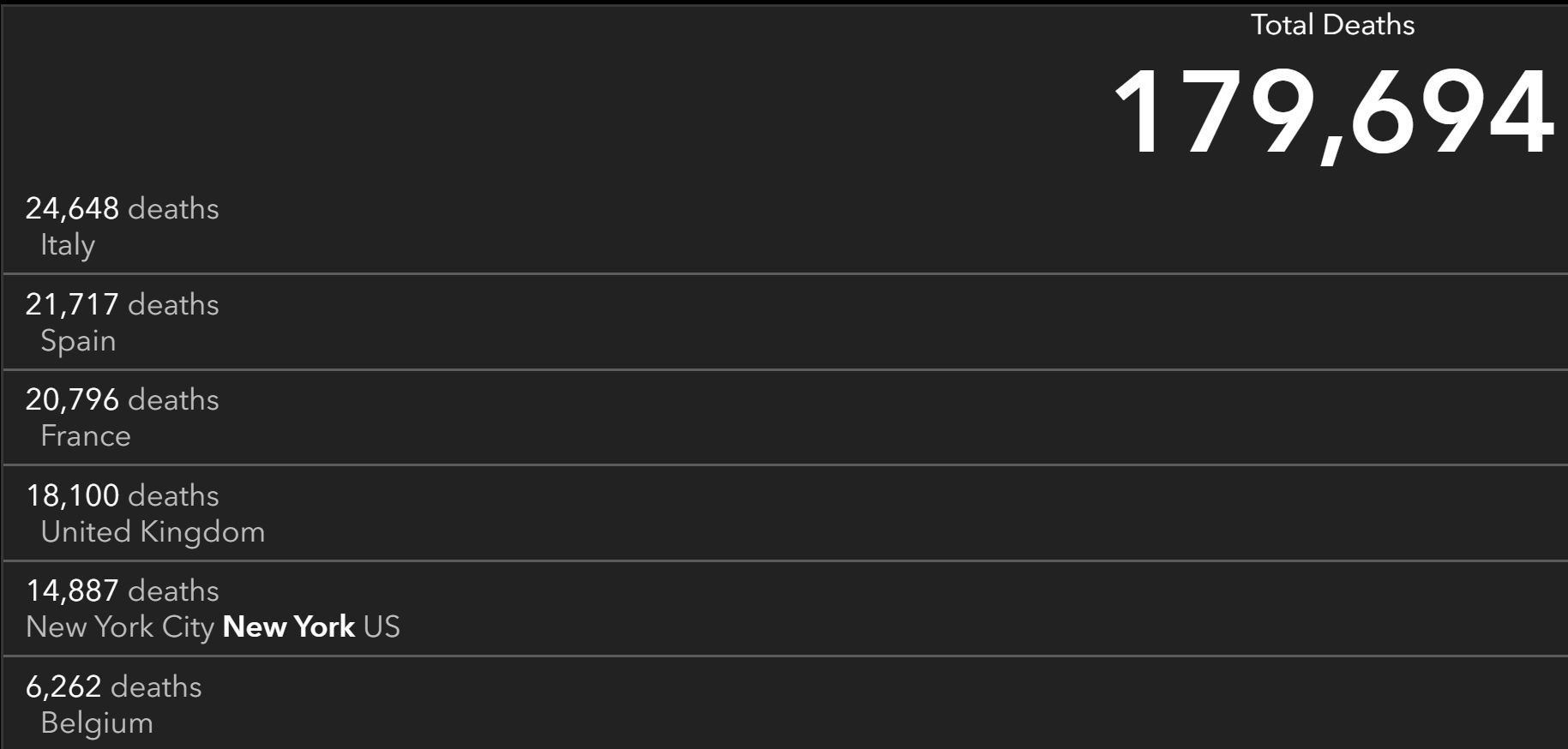

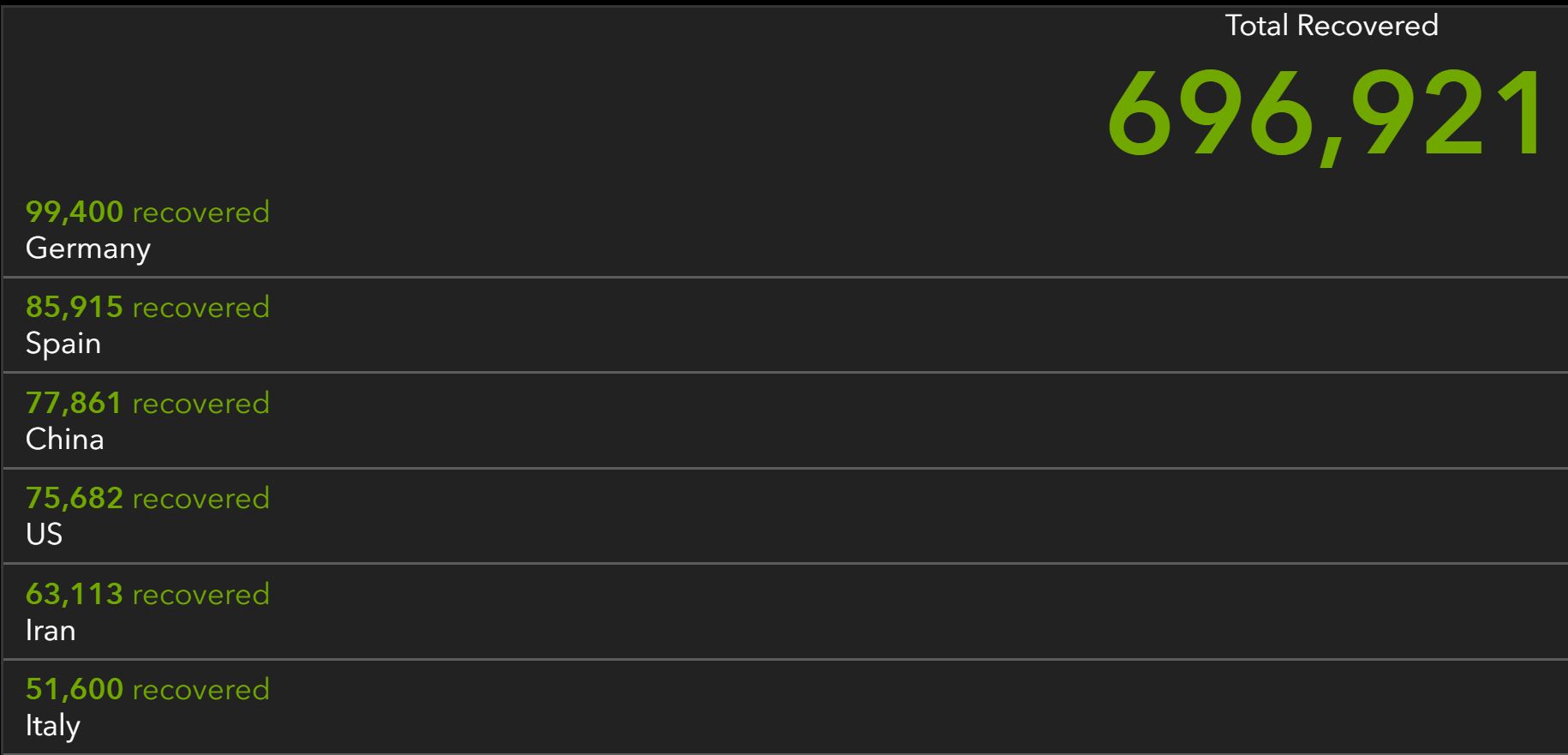

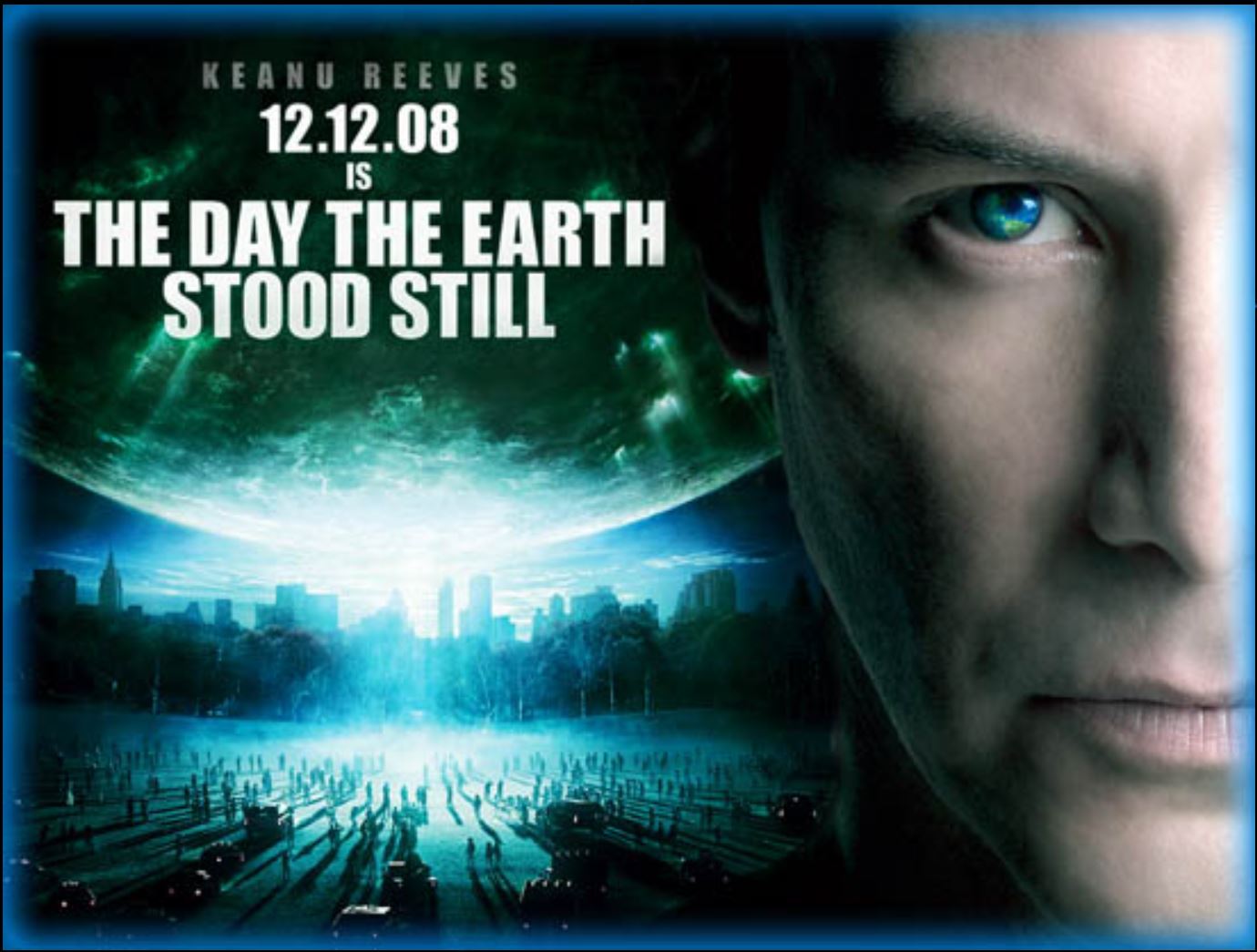

The year 2020 has been one of the most constrained where we have experienced (and continue to experience) how the COVID pandemic has seized our everyday lives. I have written a few articles on COVID (https://columbusbee.blog/2020/03/28/my-gut-feel-against-the-virus/ and https://columbusbee.blog/2020/04/22/the-day-the-world-stood-still/) as well as how it impacted our lives (https://columbusbee.blog/2020/07/25/life-is-a-beach-first-of-two-parts/ and https://columbusbee.blog/2020/09/07/life-is-a-beach-second-of-two-parts/) but I haven’t really touched on how the same has affected our mental health. There is no denying that the restricted freedom, fear of contracting the disease, anxiety of what the future holds, paranoia that every single person you meet outside may be a potential carrier, and depressing news splash on our faces every waking hour (I dread reading the papers nowadays, anticipating what new inequities and abuses are committed during these trying times) are just some of the stuff that messes up our heads. Not to mention those who worry where to get their next meal, when they can find work again or get their business up and running, and how they can get basic services such as medical attention given the roundabouts that they have to go thru to meet these necessities only add up to the mental toll. Depression is real, each and every one of us is vulnerable.

Cotton and I meeting a friend at Starbucks

We use only about 10% of our brains and depression and anxiety occupying so much space do not make a healthy, balanced mind. It’s madness, right? How much more if one is already suffering from a fragile head? We may have our own coping mechanism, but what about those who do not know how to cope at all? Shrinks are expensive, and the concept of going to the shrink in a third world country is non-existent, the mere idea can be met with contempt. I remember that when Miriam’s (https://columbusbee.blog/2019/09/21/remembering-miriam-defensor-santiago/) meeting with a shrink in the US was dug up and used by her political opponents against her during the 1992 Philippine presidential election by unfairly branding her as “Brenda” (brain damaged) that partly costs her the presidency, such ignorance would be offensive by today’s standards (but gives me comfort and hope that a quarter of a century later, this somewhat parochial and bigoted third world civilization has evolved and started to embrace the worldly view that taking care of one’s mental health is nothing different than looking after one’s physical health, that it is ok not to be ok). Shaming people for seeking help should never be tolerated, much more use against them for shameless gains.

Candy and I waiting for our turn at the vet clinic. Isn’t she pretty?

My global manager once asked me how I was coping with the lockdown, knowing fully well that I love to travel. I told him that all my flights, both local and international, have been cancelled. As I’ve mentioned in one of my articles (https://columbusbee.blog/2020/02/23/italy-how-thou-i-love-thee-let-me-count-the-ways-part-1-of-2/), my feng shui for 2020 forecasted that my spirit essence is weak (which actually was true, where there were points in time last year where I doubted myself and my capabilities) and lots of travels were encouraged to lift up my spirits. I was due for a European tour last May, partly to do some soul searching and enriching by returning to Assisi on a supposed brief spiritual retreat. That didn’t happen, same with some local travels that were also booked. I then realized that I didn’t really answer his question, where all I can muster was to say “same old, same old.” This is now my opportunity to share how I am coping with the pandemic (hope he reads this) and how I’m taking care of my mental health.

Cotton and Candy when they were still a few weeks old

I just got my Fortune and Feng Shui book for 2021 and it says that both my life force and spirit essence would be very weak. From a mental health perspective, that does not sound very good. But same as last year, I cope with by writing thru this blog. It helps me unload my thoughts, views, and perspective, which I personally believe frees up space in my brain in the same manner as how we unburden ourselves emotionally thru sharing our problems with family and friends. Not only that it helps make space for something positive, but also the psychological effect when good comments flow in, such as the one below that was posted in the blog today. Telling someone that he has a gift is a gift itself, like a ray of light in an otherwise dark and gloomy skies. Imagine how that appreciation affects me mentally.

I learned from an early age that having dogs bring a different kind of happiness. Happiness is a state of mind, and what more gives us happiness than unconditional love. Dogs do that. They give us unconditional love and so much joy (particularly during puppy stage) that they won’t be called man’s best friend for nothing. That’s why it pains us when they passed on, which in my case, took me about a couple of years before I got my furbabies in 2020 since the last one, and more than a decade past before I got the last one. Knowing that the prospect of travel in 2020 is bleak, I decided to get myself a loyal companion to lift up my spirits and went for a maltese. His name is Cotton.

Cotton in his pen, yawning. Isn’t he a handsome pup?

Having been a quarantine furbaby, Cotton hasn’t developed a sociable personality. Though he considers my apartment as his kingdom where he reigns supreme, outside, he’s very shy, nervous, and timid. When I brought him to my sister’s place to play with his cousins (my sis has a maltese and a mini poodle), he just stayed in one corner, head down, and unmoving, even when his cousins were trying to play with him. When I first brought him to the groomers, the attendant told me that he just lied flat on his tummy while being bathed, like in a submissive position, afraid to stand up. When I brought him to meet a friend, he just lied on the floor the whole time that me and my friend were having our Starbucks drinks. I’m afraid he’s going to be a social pariah.

Cousins Finn (maltese) and Teddy (mini poodle)

Then I realized that Cotton may be supporting my mental health but I’m not doing anything for his. That’s when I decided to get his companion and went for a toy poodle. Her name is Candy. On the way home when I got her, she connected right away. She was sweet and licked my arm while lying on my lap. Unlike Cotton though, the first few days at home were hard and difficult for me coz she has been excreting liquid poop (yes, as in watery discharge) that I have to clean up the mess first thing when I wake up in the morning and when I get back from work in the evening. Cleaning up does not only mean wiping the floor and disinfecting, but also washing the paws. Worried that she has been suffering from diarrhea for days since I got her (I initially thought that she was just stressed out from her new environment as well as it might be due to a change in dog food), I decided to bring her to the vet to have her checked and tested and that’s when I learned that she contracted coronavirus.

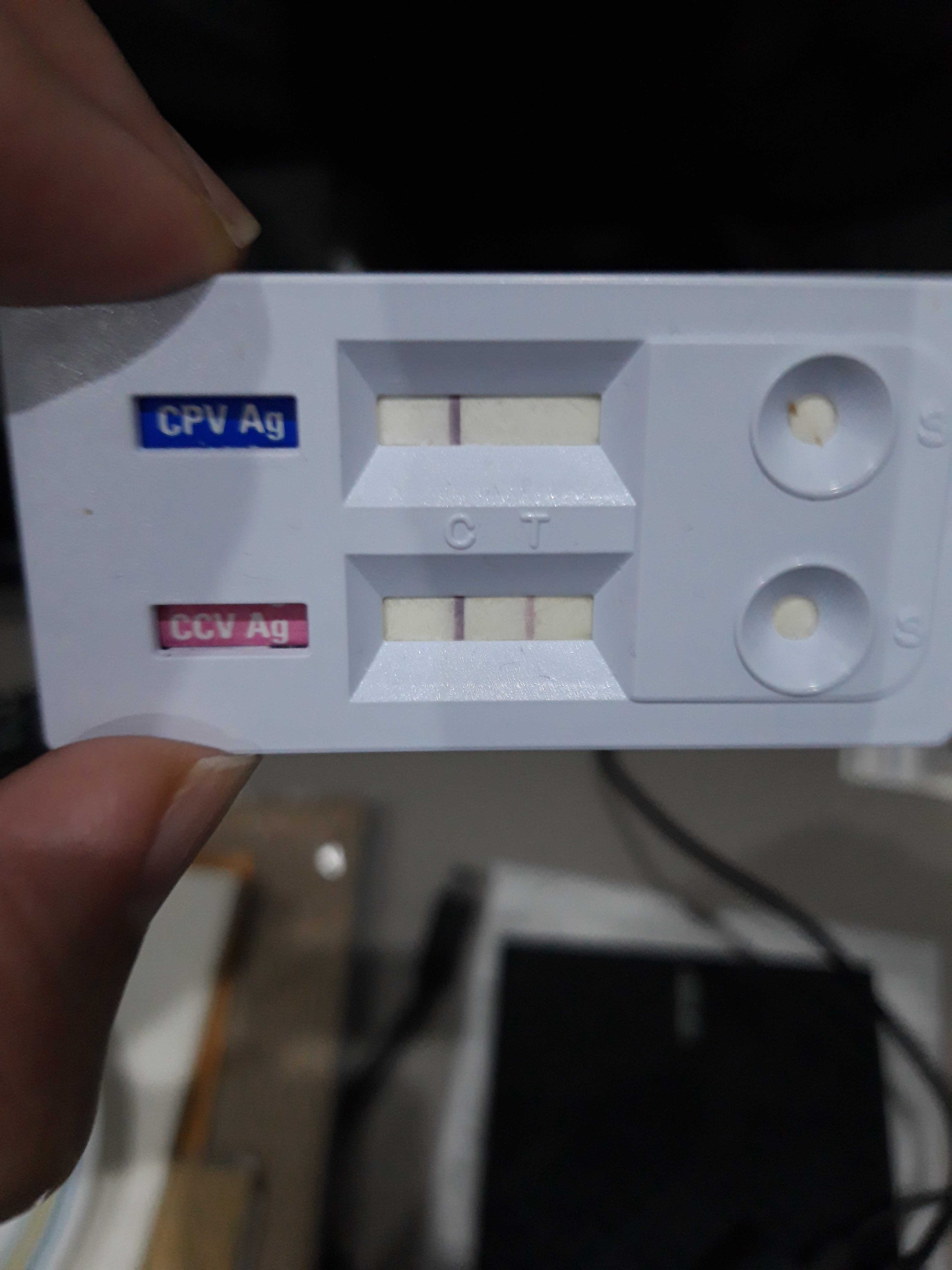

Twin test results of Candy. Top bar is for parvovirus (single line means negative) and bottom bar is for coronavirus (double means positive).

You might think, “Oh no, COVID!,” and that I may also have contracted it too. Nope, it’s not COVID, and no, I don’t have it. Coronavirus in dogs (canine coronavirus is the more appropriate name) is different than what we humans have. Whilst the virus looks similar (with spikes that look like those in a crown, hence the term corona), the strain only infects dogs where the digestive system becomes compromised (unlike in humans where it’s the respiratory system that gets affected). It’s not contagious to humans but can get passed on to other dogs (which I suspect she got when she was staying with the seller awaiting delivery where there were other puppies as well from different breeders for rehoming). Good thing Cotton did not contract it, given that both have shared a pen for a few days. During that first visit to the clinic, the vet said that the virus is self-limiting, meaning that it will just clear on its own in a few days or weeks since just like any viral infection, there is no cure (only prevention thru vaccines). So she prescribed some dog food made specially for digestive care as well as probiotics (yes, dogs need probiotics too). But her condition worsened, where not only her diarrhea has not stopped, but also vomited her food, became lethargic, and lost her appetite (she has a huge appetite earlier, even when she already has the virus). So I decided to confine her in the animal hospital where fluids and minerals can be administered thru IV (intravenous) to keep her constantly hydrated, with occasional forced feeding (as she refused to eat) to get some food to her stomach, and to manage the symptoms thru antibiotics (antibiotics do not kill viruses, it only manages the symptoms such as diarrhea).

(Left) First few days of Candy on hospital confinement; (right) last few days in the hospital where she has regained some of her strength and good spirits

Ten days of confinement later, she was discharged and I brought her home. Poor Candy, she spent her 10th-11th week (since birth) being sick and 11th-12th week on hospital confinement. I was just glad and relieved not only that she tested negative for parvovirus (that’s the most deadly infection among dogs, my last one a couple years back died of parvo) but her coronavirus has cleared. Her poop also started to form. I never thought I would be so happy to see solid poop. She has regained her appetite and she was back in her playful mood. Cotton was also glad she was back.

Candy on the vet table for her shots

You might be wondering, with all these stuff that I have to go thru, worrying about my dogs ability to socialize or when they get sick or the day-to-day handling of their needs while also going to the office to work, how would that help me with my mental health? Isn’t that something more to concern about that one is better off without? True that it requires a lot, both physically and financially (you need to have a budget for the upkeep), but what they do for me mentally and emotionally is very much rewarding. I don’t see caring for my furbabies as a mental burden. I see it as a way to fill my thoughts and emotions with something more than stuff that makes up a depression. I would rather fill that space in my brain with more of these types of worries and concerns, than let it sink deeper into black hole or oblivion as a consequence of the lockdown and/or the stress that comes from work. Caring is loving (and holds true conversely), and what more puts us in a blissful state than love? Knowing that you can still find or give love during these dark times? The unconditional love that these furbabies give back is just gravy.

Resting after some rough play

So as we usher the new year, think about your own mental health, how to achieve that balanced mind. A healthy mind and body, as well as soul, make whole, complete self. If you think and feel incomplete (regardless whether you’re single, married, “it’s complicated” but still find yourself thinking that there’s still something missing in your life), then maybe God created dogs to fill the void. You can then say to your furbabies “you complete me.” They will still love you back even if they have no idea what you’re talking about.